Truth Must Come First

Nearly two months after my trip to Montgomery, I still find myself thinking about the experiences I had there many times every day. The mental images and emotions are just as vivid as if it were yesterday. But with time I’ve gained enough distance to analyze the elements that made such an impact on me.

After visiting The Civil Rights Memorial Center, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and The Legacy Museum, The Museum Group had the extraordinary opportunity to meet with Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy.

Our relaxed meeting was an honor beyond words. As Father Thomas Keating said “The effectiveness of action depends on the source from which it springs.” I cannot imagine a more patient, persistent, wise, humble, and compassionate source than Bryan Stevenson. Many of my reflections stem from our conversation with him, and the wisdom he shared with us.

As I continue to think and talk about my experiences in Montgomery, three observations keep emerging.

1) None of the sites was a museum or memorial “as usual.”

Perhaps that’s because the Memorial and Legacy Museumwere conceived and planned by EJI staff members. People who are steeped in the content, who live the mission-but don’t have experience designing museums or memorials. They exemplify the brilliance of beginner’s mind.

The EJI team had the scholarship down and knew what they wanted to say. They began working with a well-respected national firm. A firm that had designed many museums and had their own exhibit development process. After six months Stevenson and his team wound up letting them go. “Yes,” he said, “we didn’t know what we were doing, but we had a vision.” A vision based on decades of experience working with prisoners and their families to overcome a system of modern day enslavement.

EJI staff wrote every word and designed every interpretive element. Then they worked with filmmakers, videographers, graphic designers and others to bring their vision to life. They had a clear goal: to spark conversations and to create a consciousness of “Never again.”

As their initial design for the Memorial took shape, they realized they could make it even stronger in two ways. They created a narrative path for visitors to travel and used art to evoke deep personal responses.

During our visit, I had a visceral reaction, stopping in my tracks when I saw Kwame Akoto Bamfo’s signature sculpture: an auction where enslaved people are being separated from their families.

As I moved closer to read the first interpretive panel, I stood just feet away from the auction block. With 147 licensed slave traders in Montgomery, scenes like this played out repeatedly less than a mile from where I stood.

The next day, as we discussed unconventional approaches to experience design at the Memorial, the Legacy Museum and the Civil Rights Memorial Center, a TMG colleague said “Many museums are afraid to tell it like it is.” But neither EJI nor the Southern Poverty Law Center censor themselves or the stories they tell.

Why are museums so afraid of offending people with the truth?<

What makes neutrality the goal in museum interpretation?

Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel implores: “We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor. Never the Victim.”

2) Narrative weaves poignant stories together, planting them in our minds to take root.

Stories and images of brutal violence and random killings hit me with a gut wrenching force, leaving me with indelible memories. Bryan Stevenson says that while the North won the Civil War, the South won the narrative war. This sent me to my dictionary where I found narrative defined as “the presentation of a particular situation in such a way as to reflect or conform to an overarching set of aims or values.”

This has never been more relevant than now, when people of color are presumed to be dangerous and guilty. The narrative of racial difference is as pervasive in America today as it was during Jim Crow. Slavery and segregation have been outlawed, but did not end. They evolved into our present systems of mass incarceration and economic inequity-a message the Legacy Museum conveys with great power.

With my new understanding of narratives, I can see that they don’t always rely on words. Sometimes the most vivid descriptions are created with objects that possess a powerful presence.

The narrative path through the Memorial leads you through four corridors.

As you climb to the first one, you see coffin-sized monuments made of Corten steel, stained by oxidation. Mounted at floor level, they force you to confront the names of human beings and the dates of their deaths.

In the second corridor, the floor starts to descend. You see the bodies rising up.

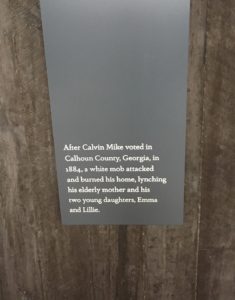

In the third corridor, you’re literally shadowed by the monuments hanging over you. They’re so high that you can barely read the names. But mounted on the walls are short narratives about individual victims and the capricious “reasons” for their deaths.

The fourth and final corridor is a memorial to the thousands of unnamed victims of racial terror lynchings. The EJI had such strict criteria that only names documented by at least two sources are listed in the memorial.

Approaching the exit, you come face-to-face with three women who boycotted busses and challenged racial segregation. This sculpture adds to the narrative by honoring women who lived where the memorial now stands, ending with the words, “You are standing in the neighborhood where modern civil rights activism in America was born.”

Guided by Justice, Dana King

3) The visitor experience includes authentic calls to action.

In Monument Park you see duplicate copies of every one of the 840 monuments hanging in the four corridors. They lie flat on the ground, like coffins, waiting to be reclaimed by each of the counties where the documented lynchings took place.

When we asked Bryan Stevenson if any had been claimed, he told us that 300 counties have already called. But before collecting their monument, a community must take two steps towards reconciliation.

- First, they must do research and erect markers about victims and perpetrators of racial terror lynchings. (This requirement is rooted in EJI’s own experience. When they first tried to place markers in Montgomery, the Alabama Historical Society refused to grant them permission. The information, while accurate, was too controversial. Markers were finally installed in 2013.

- Second, any county claiming a monument must hold a Racial Justice Essay contest for local high school students.

At the Legacy Museum you see rows upon rows of large glass jars holding soil of every imaginable color and texture. Volunteers collected the earth in each county where lynchings took place. Carefully, according to guidelines provided by EJI. Respectfully, as a profound way for the living to honor the dead.

At the Civil Rights Memorial Center, the call to action is personal. They invite visitors to place their names on the Wall of Tolerance with these words: “The wall records the names of people who have pledged to take a stand against hate, injustice and intolerance. Those who place their names on the wall make a commitment to work in their daily lives for justice, equality and human rights, the ideals for which the civil rights martyrs died.”

As you add your name, it appears on a large interactive screen along with hundreds of others. This is a powerful image to take with you when you go out into the world.

Truth Telling

To me, these memorials are not celebratory reflections of racial progress. Instead they are challenges to see and acknowledge that racism is still our nation’s greatest sin.

Bryan Stevenson’s words-“truth and reconciliation are sequential”-keep reverberating in my mind. Truth must come first. This makes me think that museums must be more courageous in speaking the truth about the histories they tell and the objects they show. They must be bolder in shining a light on the shameful elements of institutional racism and the subtle signs of othering that exist in their collections.

Those of us who work in and for museums must be more courageous about stepping outside our bubbles to see the intersections of injustice. We must show up to use whatever privileges we have as members of dominant racial and religious groups, whatever benefits are owed to our gender and sexual orientation, to stand up for our brothers and sisters. We must speak truth to power to chip away at white supremacy however it exists in our own communities.

And whatever institutional or individual courage we show, we can be sure it will pale in comparison to the sacrifices and steadfast perseverance shown by those who marched before us.

-Daryl Fischer

Thank you for sharing our journey to Montgomery in these three blog posts.

Our experiences at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, The Legacy Museum, and The Civil Rights Memorial Center have changed us.

Have you visited these or other sites that made you acknowledge difficult truths about racism? If so, please share your reflections.

Thank you to all of TMG for your thoughtful review, analysis and passionate exposition. I was especially taken with the reaction and response provide by Daryl Fischer. These facilities are different indeed, tackling real issues in dramatic and truthful ways – hopefully ones that can serve as examples for us in future work.

Thanks, Jim, for your feedback. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the Legacy Museum and the Civil Rights Memorial Center have inspired us with their bold approaches to telling hard truths that we must face. Now, once and for all. Now, more than ever.